“Deakins’ negatives are not accompanied by an exhaustive set of contact sheets. A digital contact sheet will therefore be made with a scanner before being digitised. This will be a more lengthy process than the Ravilious collection requiring more time allowance.”

The statement above was the shortened version of my project brief for Beaford Arts Hidden Histories, a project funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund and Leader 5 North Devon. Contact sheets do not exist for Roger Deakins work, he did make them but cut them into strips and slotted them into negative bags with numbers removed. Although his contacts need preserving, and ultimately digitising for the archive, they are useless for the digital database without being able to identify unique negative numbers.

Unlike Ravilious, there was no numerical labelling of Deakins’ negative bags, so I started the process of making new ‘digital’ contact sheets with the first of four folders of negative bags. These negatives were housed in their original archival, but translucent, paper negative bags, often with written notes marks and connotations. Under close inspection on a lightbox I could see that negatives were often filed in a random order, sometimes up-side-down or reversed, sometimes the same number appeared twice and on one occasion 3 times. It became clear that a negative bag didn’t necessarily contain one film, one specific shoot, location, person or group. In comparrison to Ravilious’ contacts there appeared a randomness, or chaos, to his negative filing. However on closer inspection a thematic approach eg ‘railway stations’ had been taken. The negatives themselves were generally in very good condition for their age, with only a few which had stains through poor fixing or washing.

The negatives would ultimately need re-bagging in a comparable fashion to James Ravilious, clear plastic archival bags (this would also be necessary for making digital contact sheets through scanning), so in consultation with Beaford and the Devon Archives Conservator, I went about consolidating the negative strips and making new collections based on single films. This was very time consuming because Deakins (like Ravilious) often loaded his own 35mm canisters of film from a bulk roll so the first negative on a roll could be any number from 0 to 40 and each roll could be any length from approximately 12 to 38 frames.

The negatives would ultimately need re-bagging in a comparable fashion to James Ravilious, clear plastic archival bags (this would also be necessary for making digital contact sheets through scanning), so in consultation with Beaford and the Devon Archives Conservator, I went about consolidating the negative strips and making new collections based on single films. This was very time consuming because Deakins (like Ravilious) often loaded his own 35mm canisters of film from a bulk roll so the first negative on a roll could be any number from 0 to 40 and each roll could be any length from approximately 12 to 38 frames.

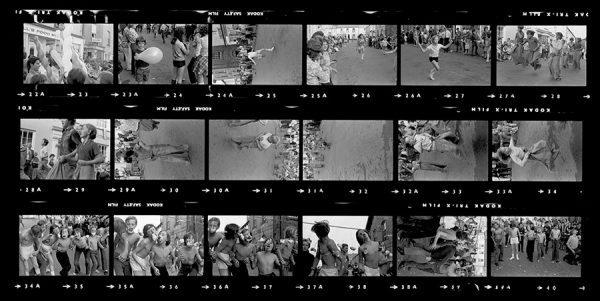

I made the new digital contact sheets through scanning Deakins’ negatives, held within clear file pages, on the project’s Epson 800 Perfection V800 scanner. This time is was set to scan transparencies at 600 dpi, large enough to be able to identify the place and/or subject in a photograph and to see those images in the context of the photoshoot, but small enough to make physical and data base storage practical. It was also within the independent consultant’s recommendation and the scanner’s linear relationship between quality and time: whilst a negative sheet was being scanned there was just enough time to make minor adjustments to cropping, exposure and contrast of the previously made digital contact sheet.

This was the most exciting and rewarding part of the project to date because I was able to see, as a positive image, that which had only existed as a 35mm negative since 1972. I wonder how many great images from yesteryear have been lost, because the 36x24mm negative or contact image had been brushed aside or unnoticed through their size, or poor exposure. Seeing each of Deakins’ images, with corrections made to exposure and contrast, 24cm wide on my computer monitor brought them to life. If only this technology was available when I was shooting film myself!

I had earlier written how Deakins’ negatives themselves were generally in very good condition for their age; however once the digital contacts had been made it became clear that some suffered from poor developing and light leaks (and in the case of the example above, double exposure), reminiscent of Robert Capa’s celebrated D-Day Landing photographs in the example below. After discussing the issue with the Hidden Histories coordinator we decided, rather than attempting the difficult and time consuming task of perfecting these faults through Photoshop, that we should embrace their endearing, nostalgic qualities; only digitally correcting damage to the negatives post processing.

I had earlier written how Deakins’ negatives themselves were generally in very good condition for their age; however once the digital contacts had been made it became clear that some suffered from poor developing and light leaks (and in the case of the example above, double exposure), reminiscent of Robert Capa’s celebrated D-Day Landing photographs in the example below. After discussing the issue with the Hidden Histories coordinator we decided, rather than attempting the difficult and time consuming task of perfecting these faults through Photoshop, that we should embrace their endearing, nostalgic qualities; only digitally correcting damage to the negatives post processing.

Digitisation Part 3 Making copies of negatives

Digitisation Part 3 Making copies of negatives