My thoughts as Hidden Histories digitiser and as a photographer with a wealth of black-and-white photography experience on the development of both photographers:

Although these are simply thoughts as they are unsubstantiated because there is very little written evidence for either photographer in terms of their creative/artistic/photographic development, either through their own notes or diary or through academic research.

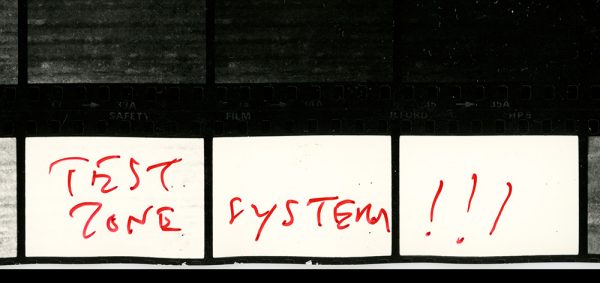

Ravilious was a gifted image maker in terms of composition right from the start of his time at Beaford, this was clearly due to his art training and family nurturing. However, his technical ability, image exposure and developing of the negative, is inconsistent and errs to the under exposure/under-development side. This produced thin negatives that were often difficult to print. Ravilious said of himself that he is ‘badly self-taught’ and he was scathing about the technical quality of his early pictures through the first decade of the Beaford project. He talks later about using Ansel Adams Zone System in an adapted format, essentially exposing for the shadows and developing for the highlights: it was interesting to come across a contact sheet RAV-02-1456, from November 1981, which has test shots for the use of the Zone System.

This is followed by a number of well exposed and well developed rolls of film including RAV-03-1461 which holds some landscape photographs reminiscent of Adams own. Although Ravilious surprisingly deemed these images as only ‘fair’. There is certainly greater consistency in his second decade, after this Zone system revelation. By this time, he had also acquired noncoated lenses for his Leica cameras which would give him a greater range of tones, and the Ilford 400 ISO film he used had been updated from HP4 to HP5 from 1977. His use of the same film sensitivity throughout his time at Beaford is often the mark of a good photographer, taking a lead from his photographic inspiration Cartier Bresson, and using film speed that he could really get to know intimately. This is demonstrated time and again with excellent use of shutter speed to freeze movement that mattered like a person’s face but allow movement in the frame from things like a football, shuttlecock, Wellington (RAV-03-1713-59A) or moving animals etc. A good example of his masterly technique is RAV-03-1526-22 when he pans a reveller dressed in drag sat in a pushchair being raced at a carnival, the pushchair and rider are frozen in the picture and yet the hedge behind seems to blur through his camera movement. Another good example is on contact sheet 1985 where Ravilious sets up his camera on a tripod in school and uses a slow shutter to emphasise the number of children in the overflowing classroom.

Looking again at Ravilious’s chosen ‘Best’ and ‘Good’ image distribution throughout the archive, he chooses a greater percentage from his early years despite his poor technical ability at the time and his admittance that many of his images from this era would be very difficult to print. I have found that an advantage of digitising the negatives is that a greater range of tones can be captured in a RAW file than is possible in a print; therefore it ought to be possible ultimately to make better ‘digital’ prints from some of these earlier negatives that Ravilious might well have struck of as ‘Fair’ or ‘Poor’ because the exposure or development dictated it thus.

Deakins was also art trained, a gifted painter at school he came to Beaford at 21, fresh from Bath Academy of Art. Working on the Beaford Archive was to be his ‘gap-year’ before pursuing his passion for cinema at the National Film School. Deakins was not at Beaford for long enough for me to discuss development and, of course, without a consecutive timeline of photographs it would be impossible to make any assessment. However, what we do have is a remarkable archive, the beginning, of what was to become an incredibly successful career at the highest level in cinematography. There are certainly innumerable references, within this year of images, which demonstrate a cinematic leaning and dramatization of the subject. There is a continuous searching for style through Deakins work; a lot of experimentation, pushing himself to try making images outside of his comfort zone and his technical ability as a way of learning and improving on his ‘seeing’ and his craft. Deakins also pushed the boundaries of ‘taste’ or ‘acceptability’ of an urbanite choosing to unsympathetically document a fox hunt and a stag hunt and kill, a cow slaughtered in an abattoir and cut into pieces for the butchers, death at lambing time and chickens killed, plucked and ready for the table. These images were shot in a cold but honest, undramatised fashion, accurately recording the grittier side of typical rural life. See above: Stevenstone Hunt, Taddiport 1971 – by Roger Deakins for the Beaford Archive.

Myth Busting

I’ve come across many inconsistencies where we read, and we think we know something about James Ravilious but in fact the truth is less certain. For example, it is said that he never used flash, and yet contact sheet RAV-02-1605 from an early January morning in 1983 women are pouring milk into bottles before delivery. I can’t say for absolute certain that Ravilious has used flash but the lighting in the workshop where the women are photographed would be extremely uncomfortable and difficult to work under. We were also told that he never set any of his pictures up, however it’s hard to believe examples like RAV-02-1718-21, RAV-02-418-10A, RAV-02-683-37 and RAV-02-1123-2 have simply arranged themselves.

-

-

RAV-03-1605-41 Documentary Photograph by James Ravilious for the Beaford Archive

-

-

RAV-03-1123-2 Documentary Photograph by James Ravilious for the Beaford Archive